Wood is a natural, organic composite material primarily composed of cellulose fibers within a matrix of lignin. More specifically, wood consists of:

Cellulose provides structural stability and strength. It also lets wood bend a little, giving it sway in the wind.

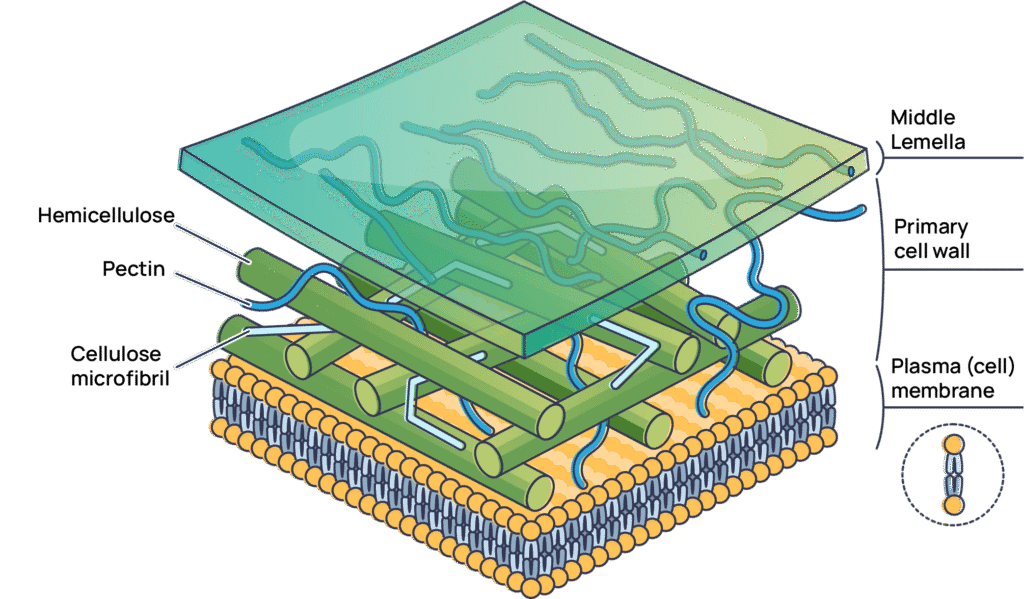

Lignin, which resists compression and is a binder for all the cellulose molecules. Lignin acts as the chief “wood substance” in wood cells. Lingnin acts as cover for microfibrils.

Hemicellulose, another binder or agent that works as a polymer for wood cells and makes up about 30% of wood fibers and cell walls.

Water, the same stuff you drink.

Extractives, which are the impurities and other organic materials that give wood its color, smell, other features. Like syrup from maple trees or sap.

Carbon (~49%), hydrogen (~6%), oxygen (44%), nitrogen, and ash, round out the rest of a tree’s wood fibers and cell walls.

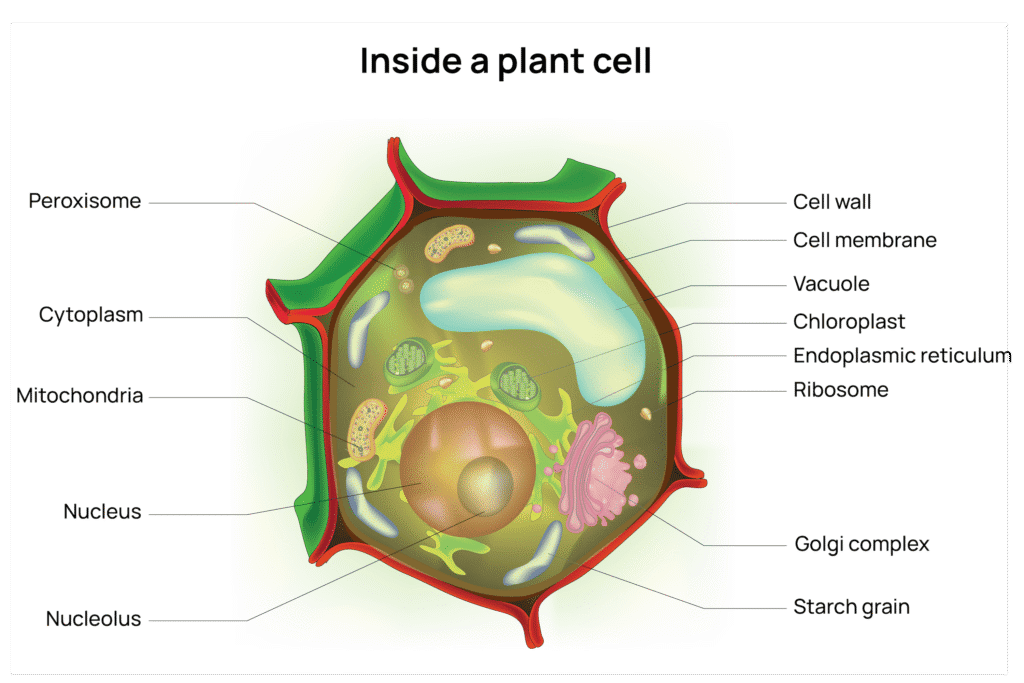

Cell structures for plants and wood

Inside wood’s cell walls and tree growth rings

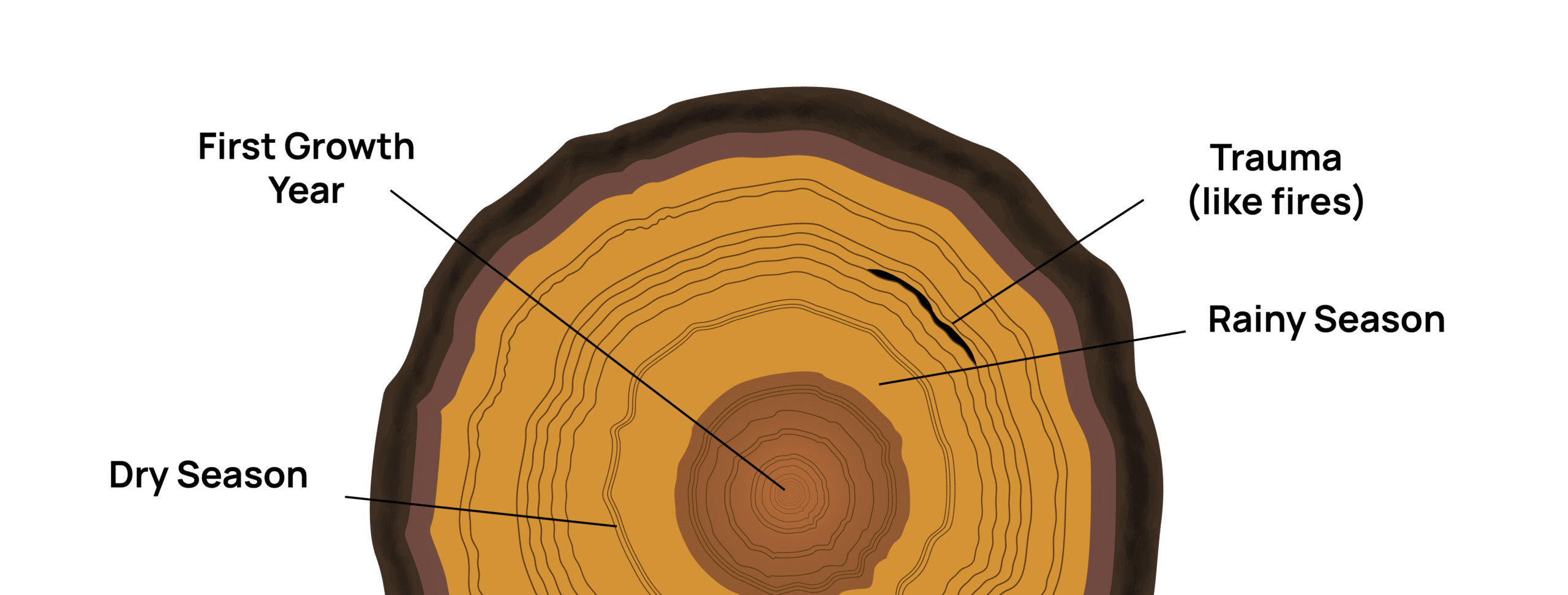

If you imagine a cross-section of a tree like the cross-section of the Earth, there are several different layers. You’re probably familiar with growth rings as they indicate the age of a tree. Growth rings also indicate how much a tree species grew in a given growing season.

But there’s more to wood…

Growing sapwood expands a tree

Foremost is sapwood. Outer ring porous hardwoods are very active. They’re growing and moving water-soluble sugars and moisture content through the tree.

- Sapwood stores nutrients and expands the tree for new growth.

- Sapwood isn’t as desirable for human use, but it does have use cases once treated.

- Sapwood makes for flexible wood needs and it’s light, so veneers and stains take to it with unique applications.

Eventually, sapwood cells die. But rather than fall off, they’re encased in new growth.

Sapwood becomes hardwood

Sapwood ultimately becomes the older, more interior rings known as heartwood. These rings are not living, but they do a lot of work, providing support to a tree. Kind of like a steel beam in a skyscraper. But unlike building construction, this “beam” grows as the tree grows with an expanding wood structure of spent sapwood.

Heartwood is, as the name suggests, the heart of the tree. It’s used for woodworking, flooring, cabinetry, and building construction. It’s durable, darker, and produces tanning, resin acids, oils, and other extractives that can be used for other materials or uses.

Earlywood and latewood

Dendochronology of a tree

When looking at sapwood and heartwood you’re looking at the vascular cambium growth rate inside the tree’s growth rings, otherwise known as its dendochronology. These rings are defined in part by earlywood and latewood (sometimes called springwood and summerwood) and are the two distinct zones in any annual ring of temperate-zone trees.

Earlywood is most common in the spring as its primary growth season. In softwoods, earlywood cells (tracheids) are larger in diameter and have thinner cell walls, making the wood lighter, softer, and more permeable.

In ring‐porous hardwoods, earlywood vessels are larger and more numerous, giving this zone a more open, porous appearance.

Latewood is common in the summer, during a living tree’s slower secondary growth period. In softwoods, latewood tracheids are smaller in diameter with thicker cell walls, resulting in a denser, darker band.

In ring‐porous hardwoods, latewood has smaller, less frequent pores, creating a tighter, more solid appearance from the wood’s cell walls outward.

Wood’s chemical composition is perfect for our needs

Done well, wood species sourced close to the project further reduces climate impact. Foreign wood species, for instance, would require significant transport costs by sea that reduce some of the carbon offset impact of choosing wood.

Wood is a lot of things:

- Profitable

- Versatile

- Carbon-storing (Earth’s “natural carbon sink”

- Infinitely renewable, with managed forestry

- Recyclable

- Durable

- Energy-efficient

- Attractive

- Biodegradable

- Biodiverse

- Biophilic

Unlike rare earth minerals and metals, wood grows and regenerates in human-friendly spans of time. We can produce a lot more wood in 20 years than we can metal.

The Earth does not produce “new” metal each year in any meaningful way. What we consume annually in metal is about 3.2 billion tons. The metal we mine is mostly iron ore is bound in time cycles that span millions of years across volcanic activity, hydrothermal deposits, and sedimentary formation. A tree can become mature for use as timber in about 10-20 years, depending on the species, and merely requires planting.

There are also a lot of different types of woods from various tree species. (Timber and building material pros use the words “softwoods” and “hardwoods”, but those labels have more to do with how the tree species reproduce.)

- Hardwood trees are angiosperms that produce flowers. Like maple or oak trees. These hardwood trees make for great building materials in furniture and interiors.

- Conifers—such as spruce and pine—are softwood trees that typically bear cones and have needle- or scale-like leaves. Softwoods are widely used in construction for framing lumber, mass timber beams, and as raw material for engineered wood products such as particleboard and MDF, often mixed with hardwood fibers.

There are other differences and some exceptions, but the general rule is that deciduous trees are usually hardwood trees, and conifers are softwood trees.

Contact us with questions.